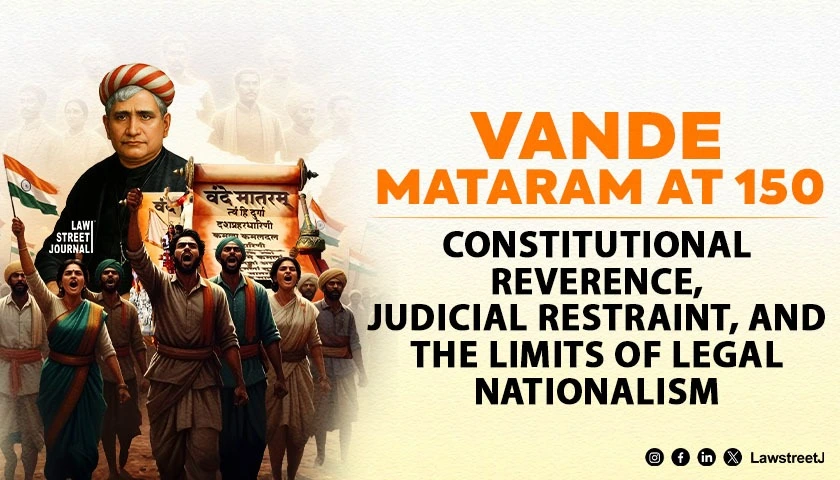

New Delhi: As India marks the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram, the nation is compelled to revisit not merely a song, but an unresolved constitutional question. Penned by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee on 7 November 1875 and later enshrined in Anandamath, Vande Mataram emerged as one of the most potent cultural expressions of India’s freedom struggle. It animated mass movements, inspired revolutionaries, and came to embody the moral imagination of an awakening nation.

Yet, despite its unparalleled historical resonance, Vande Mataram occupies a paradoxical position in independent India. It is emotionally sacrosanct, yet legally understated. The sesquicentennial moment has thus reopened a long-standing debate: whether the Indian constitutional order has fully reconciled the song’s civilizational significance with its liberal democratic commitments.

The 1937 Compromise and the Politics of Truncation

The contemporary status of Vande Mataram cannot be understood without reference to the 1937 decision of the Indian National Congress to formally adopt only its first two stanzas. Until then, the song in its entirety had served as a unifying anthem of resistance.

The truncation, endorsed under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru with inputs from Rabindranath Tagore, was justified on the ground that the later stanzas, which employ imagery of Hindu goddesses such as Durga and Lakshmi, might conflict with the religious beliefs of some communities. The decision was framed as a political accommodation aimed at preserving unity in a deeply plural society.

While contemporary political opinion remains divided on whether this was pragmatic statesmanship or cultural dilution, it is undeniable that the compromise permanently shaped the song’s constitutional journey, leaving its full form outside the framework of official national symbolism.

Constituent Assembly Recognition and Constitutional Silence

On 24 January 1950, the Constituent Assembly addressed the question of national symbols. Dr. Rajendra Prasad, presiding over the Assembly, made a solemn declaration:

“The song Vande Mataram, which has played a historic part in the struggle for Indian independence, shall be honoured equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it.”

Despite the moral clarity of this declaration, it was never translated into constitutional text. Article 51A(a) of the Constitution imposes a Fundamental Duty to respect the National Flag and the National Anthem, but remains silent on the National Song. This silence has had significant legal consequences.

The Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971 criminalises disrespect to the Constitution, the National Flag, and the National Anthem, but provides no statutory protection to Vande Mataram. As a result, the song enjoys declaratory equality without enforceable parity.

The Executive Position: Reverence Without Regulation

This legal asymmetry has been expressly acknowledged by the Union Government. In affidavits filed before the Delhi High Court in 2022 and 2023, the Ministry of Home Affairs stated that while Vande Mataram holds a “unique and special place” in the emotions of the people, no binding instructions have been issued regulating its recitation, nor have penal provisions been enacted for preventing or refusing to sing it.

The Centre further clarified that the inter-ministerial committee constituted to regulate national symbols has confined its deliberations to the National Anthem, reflecting a continued policy reluctance to legislate reverence for the National Song.

Judicial Engagement and the Right to Silence

The judiciary has repeatedly been called upon to mediate between nationalist sentiment and individual liberty. The foundational precedent in this domain remains Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala (1986) 3 SCC 615, where the Supreme Court held that compelling schoolchildren to sing the National Anthem violated their freedoms under Articles 19(1)(a) and 25(1). The Court affirmed that respect for national symbols cannot be enforced through coercion, firmly establishing the right to silence as a constitutional value.

This principle has significantly shaped later judicial engagement with Vande Mataram.

In K. Veeramani v. State of Tamil Nadu (Madras High Court, order dated 25 July 2017), the Court directed that Vande Mataram be played or sung periodically in schools and educational institutions, and occasionally in government offices, to foster patriotism. Crucially, the Court added an express caveat that no person should be compelled to sing the song if they held genuine objections. Following public debate, the order was clarified to be directory rather than mandatory, underscoring judicial sensitivity to constitutional freedoms.

More recently, the Nagpur Bench of the Bombay High Court in Pramod Shendre & Dr. Subhash Waghe v. State of Maharashtra (order dated 24 July 2024) quashed an FIR registered under provisions including Section 295A IPC, where individuals were accused of hurting religious sentiments by allegedly insisting that members of a WhatsApp group chant Vande Mataram. The Court held that isolated or coercive patriotic expression cannot, by itself, constitute a criminal offence, and cautioned against criminalising speech absent clear intent to outrage religious feelings.

Judicial Restraint and the Question of Statutory Parity

Attempts to secure statutory parity for Vande Mataram have consistently met judicial restraint. In Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay v. Union of India, petitions sought directions to accord the National Song the same legal protection as the National Anthem, relying on Dr. Rajendra Prasad’s 1950 declaration. The Supreme Court and Delhi High Court declined to intervene, observing that the Constitution does not recognise the category of “National Song” within Article 51A, and that any elevation of status must come from legislative action, not judicial fiat.

Similarly, in Shyam Narayan Chouksey v. Union of India (2018) 3 SCC 39, although the case concerned the mandatory playing of the National Anthem in cinema halls, the Supreme Court reiterated a broader principle: patriotism cannot be reduced to ritualistic enforcement, nor can constitutional loyalty be compelled by threat of sanction. This reasoning indirectly reinforces the voluntary character of reverence toward Vande Mataram.

Symbol, Law, and Civilizational Memory

The 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram illuminates a deeper constitutional tension: how should a modern republic honour symbols rooted in civilizational consciousness while remaining faithful to liberty, pluralism, and freedom of conscience? For some, extending statutory protection to the song would correct a historical imbalance and reaffirm cultural continuity. For others, its enduring moral authority lies precisely in its voluntary acceptance rather than legal coercion.

What remains clear is that Vande Mataram occupies a unique constitutional space, revered, foundational, yet legally understated. Until Parliament chooses to act, its power will continue to flow not from statute books, but from collective memory and ethical allegiance. True equality, as envisioned in 1950, may ultimately depend not on compulsion, but on consensus.

![Delhi High Court Sets Aside Arbitral Tribunal's Award Against NHAI in Highway Project Delay Case [Read Judgment]](/secure/uploads/2023/07/lj_9605_23374c2e-392c-4491-a2fe-f2f12fc5272f.jpg)

![Delhi Court Rejects Stay Request in Defamation Case Against Rajasthan CM Ashok Gehlot [Read Order]](/secure/uploads/2023/08/lj_5208_80de1ddc-d76a-4f7f-b180-408e3ae14fb4.jpg)