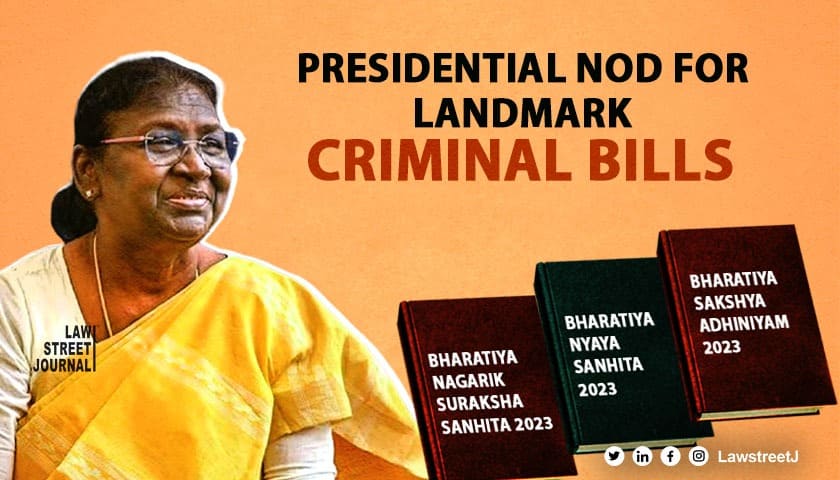

New Delhi: In a historic stride towards legal modernization, July 2024 marked a transformative chapter in India’s judicial journey. The nation bid farewell to its colonial-era criminal statutes laws that had governed the Indian legal landscape since the British Raj and ushered in a new era with the enactment of three indigenous legal codes. The Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860, the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) of 1973, and the Indian Evidence Act (IEA) of 1872 have now been replaced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA), respectively. This sweeping reform is not merely a change in nomenclature; it represents a profound shift in the philosophy underpinning India’s criminal justice system. The new codes have been designed to reflect the values, aspirations, and socio- legal realities of a sovereign, democratic India who is free from the vestiges of colonial rule. Where the old laws often prioritized the state and its authority, the new framework seeks to place citizens, especially victims of crime, at the heart of justice delivery. One of the central aims of this overhaul is to make the criminal justice system more accessible, victim-centric, and aligned with contemporary technological advancements. The BNS introduces clearer definitions and streamlined procedures to reduce ambiguity in criminal law, while the BNSS incorporates provisions for faster investigations, improved police accountability, and greater use of forensic and digital evidence. The BSA, meanwhile, updates rules of admissibility and relevance of evidence in light of modern realities, thus enhancing the fairness and efficiency of trials.

This legal renaissance is a bold attempt to simplify complex procedures, eliminate redundant colonial constructs, and ensure that justice is neither delayed nor denied. It also signifies an effort to harmonize legal processes with India’s cultural identity and constitutional ethos, promoting transparency, accountability, and equity in the justice system. In essence, the introduction of these new legal codes signals not just a legislative shift, but a visionary commitment to justice reform one that aspires to build a system that is more humane, equitable, and responsive to the needs of a modern India who has made a conscious and calculated departure from its colonial past respectively. This section delves into the comparative essence of these transitions, not as a dry legislative comparison, but as a reflection of India’s evolving legal consciousness

From IPC to BNS: Shifting from Retribution to Reform

The Indian Penal Code, drafted in 1860 by Lord Macaulay, had long served as the backbone of India's substantive criminal law, defining various offences and prescribing punishments. While it was pathbreaking for its time, the IPC increasingly struggled to address the complex nature of modern crimes such as cyber offences, organized financial frauds, and digital harassment.

The newly introduced Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) is not just a rebranded statute but it represents a conceptual leap forward. The BNS embraces the notion of reformative justice by introducing penalties that focus on rehabilitation over mere punishment. It broadens the legal vocabulary by incorporating offences relating to cybercrime, terrorism, mob lynching, and white-collar crimes, which were either inadequately addressed or entirely absent in the IPC. By doing so, it brings Indian criminal law in sync with the demands of the digital and globalized era, while retaining the core principles of justice and proportionality

From CrPC to BNSS: Towards Speed and Sensitivity

The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), enacted in 1973, governed the procedural dimensions of criminal law covering everything from the registration of FIRs to trials, bail, and appeals. Despite its procedural rigor, the CrPC was often criticized for being slow, opaque, and skewed in favor of state machinery, with victims frequently sidelined in the process.

Enter the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), a procedural code designed to recenter the justice system around the citizen, particularly the victim. With strict timelines for investigation and trial, the BNSS aims to reduce pendency and ensure timely justice. Furthermore, it encourages integration of technology through electronic FIRs, video-recorded statements, and virtual court proceedings, thereby improving both access and efficiency. More significantly, the BNSS recognizes the emotional and psychological trauma endured by victims and introduces provisions for greater victim participation, support, and protection during legal proceedings.

From IEA to BSA: A Modern Lens on Truth and Proof

The Indian Evidence Act (IEA) of 1872 was a remarkable legal document in its time, laying down comprehensive rules on the admissibility, relevance, and burden of proof. However, with the advent of modern technology and new forms of evidence, its rigid frameworks had become outdated and increasingly impractical in contemporary trials. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) is a much-needed update that reimagines the law of evidence in light of technological advancement and practical necessity. It explicitly recognizes digital and electronic evidence, DNA reports, forensic findings, and other scientific tools as vital and admissible pieces of proof. Simplification of evidentiary rules allows for speedier and more reliable trials, while the inclusion of witness protection measures ensures that key testimonies are not lost to fear or coercion. The BSA, in essence, seeks to balance the scales of justice by making evidence law more robust, secure, and inclusive of the realities of the 21st century.

BNS vs. IPC: Bridging the Past and Present

The Indian Penal Code (IPC), enacted in 1860, served as the primary source of substantive criminal law in India for over 160 years. While robust for its time, it grew increasingly out of step with the realities of a rapidly digitizing and evolving society. The IPC lacked a comprehensive framework to address modern crimes such as cyber fraud, terrorism, and transnational organized crime, and often reflected a punitive rather than a reformative approach. Enter the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), a forward-looking code that redefines crime through a contemporary lens. It incorporates new-age offences like cybercrime, terrorism, and organized syndicate activity, ensuring that the legal definitions are aligned with the realities of today’s digital and interconnected world. More importantly, the BNS pivots towards reformative justice. It introduces alternatives to incarceration for minor offences such as community service and probation thus acknowledging the potential for rehabilitation and reintegration over mere punishment. This shift marks a decisive departure from colonial-era retribution and embraces an approach more suited to modern democratic values.

Key Structural Changes

- Consolidation of Definitions: The IPC had a separate and lengthy list of definitions under Sections 6 to 52. The BNS simplifies this by consolidating definitions into just two sections (Sections 2 and 3), making the code more accessible and easier to interpret.

- Elimination of Colonial Language: Archaic references to “British India,” “Queen,” and “Crown” have been completely removed, giving the code a language that is sovereign, secular, and rooted in Indian democracy.

- Inclusion of Contemporary Offences: New offences such as mob lynching, terrorism, sexual exploitation under the guise of false promises, and snatching have been added, offences that were previously under-addressed or entirely missing from the IPC.

- Introduction of Reformative Punishments: The BNS introduces community service and probation as alternatives to incarceration for certain minor crimes, reflecting a shift from retribution to rehabilitation.

- Broadened Definitions: The concept of theft now includes intangible property, acknowledging the rise in digital and intellectual asset crimes.

BNSS vs. CrPC: Toward a Citizen-Centric Criminal Process

The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), established in 1973, provided the procedural framework for investigating and adjudicating criminal cases. However, over time, it became mired in procedural delays, ambiguity, and a lack of accountability, often resulting in prolonged justice and a system viewed as intimidating and inaccessible by the common citizen. The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) steps in to streamline and modernize the criminal procedure, introducing clear timelines for investigation and trial to combat unnecessary delays. It places strong emphasis on the use of technology, enabling features like electronic FIRs, digital charge sheets, and virtual court hearings making the justice process more efficient and less burdensome. Crucially, BNSS is markedly victimcentric. It fortifies victim compensation schemes, ensures greater participation and protection for survivors, and instils a sense of responsiveness and dignity into the procedural framework. The transition from CrPC to BNSS thus represents a shift from a system built for state control to one designed around citizen rights and access to justice.

Key Structural Changes

- New Sections Introduced (9): BNSS includes nine new sections focused on forensic evidence procedures, digital trials, and trial in absentia, reflecting a system designed for speed and scientific accuracy.

- Outdated Sections Repealed (9): Redundant and obsolete procedural elements some of which were legacies of the colonial era have been scrapped to reduce legal clutter and confusion.

- Extensive Amendments (160 Sections Modified): The BNSS amends more than 160 sections, introducing digital filing of FIRs, electronic service of summons, new bail guidelines, and strict time-bound investigation protocols. These changes promote efficiency, transparency, and accountability in the procedural framework.

BSA vs. IEA: Adapting to the Digital Age

Perhaps one of the most overdue updates comes in the domain of evidence law. The Indian Evidence Act (IEA) of 1872, though revolutionary in its time, was inadequate to deal with the nature and complexity of digital, electronic, and scientific evidence prevalent today. It lacked mechanisms for admitting DNA results, electronic communications, or forensic reports now common in modern litigation. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) brings evidence law into the 21st century. It explicitly recognizes digital and forensic evidence, establishes clear protocols for DNA, electronic records, and data retrieved from digital devices, and simplifies the rules governing the admissibility and evaluation of such evidence. The BSA also takes serious note of witness safety, introducing mechanisms for witness protection and anonymity, which are crucial in cases involving serious threats or organized crime. It also enhances the role of expert testimony, empowering courts to consider the insights of forensic and technical specialists when evaluating evidence. In short, the BSA reflects a clear understanding that truth-seeking in the digital age demands modern tools and safeguards.

Key Structural Changes

- Additions: The BSA introduces 2 new sections and 6 new sub-sections, particularly focusing on the admissibility and management of digital records, international treaties, and the expanded role of expert evidence, including forensic, technological, and scientific expertise.

- Removals: Six outdated sections have been omitted, primarily those that addressed obsolete practices or used language incompatible with modern legal standards.

- Revised & Clubbed Provisions (24 Revisions): To reduce redundancy and improve readability, 24 provisions have been revised, using inclusive, tech- savvy language that accommodates the digital chain of custody, remote testimony, and electronically stored information.

Merits and Demerits: Weighing the New Against the Old Merits of BNS, BNSS, BSA

- Modernization of Law and Process

One of the most significant achievements of the new codes is their proactive approach to contemporary crimes, including cybercrime, digital fraud, terrorism, and organized crime. They recognize the need to adapt the legal system to the age of data, devices, and transnational threats, integrating technology into investigation and trial procedures, including provisions for digital FIRs, electronic evidence, and virtual hearings.

- Victim-Centric Approach

For decades, the criminal justice process in India had been largely state-centric, often ignoring the voices and rights of victims. The new codes, in contrast, introduce a victimforward philosophy, strengthening compensation mechanisms, enabling greater participation, and providing legal safeguards to protect the dignity and safety of victims and survivors.

- Improved Efficiency and Timeliness

By introducing mandatory timelines for both investigation and trial, the BNSS seeks to counter the endemic issue of delay in justice delivery. This feature alone holds the potential to significantly reduce pendency, unclog courtrooms, and reinforce public trust in the legal system.

- Reformative and Community-Based Justice

Recognizing the rehabilitative potential in minor offences, the BNS introduces alternatives to imprisonment, such as community service, probation, and counseling. This represents a welcome shift from punitive colonial ideals to reformative justice rooted in social reintegration.

- Enhanced Transparency and Uniformity

With clearer and more standardized procedures, the new codes aim to reduce ambiguity, regional disparities, and judicial inconsistencies. The uniform structure fosters greater predictability and transparency in criminal trials across the nation.

- Accountability Mechanisms

Provisions under the BNSS and BSA aim to enhance the accountability of police and prosecution, requiring them to adhere to deadlines and ethical standards while reducing arbitrary action.

Demerits of BNS, BNSS, BSA

- Implementation Hurdles

While the intent is progressive, the success of these codes depends heavily on effective execution. The legal ecosystem comprising police, judiciary, lawyers, and administrative staff requires extensive retraining and capacity-building, which could take time and significant resources.

- Transitional Confusion and Delays

As with any major legislative transition, there is a risk of confusion during implementation. Pending cases under the old laws, overlap between statutes, and uncertainty among legal professionals could lead to temporary judicial bottlenecks.

- Risk of Misuse and Overreach

Several provisions still vest significant discretion in law enforcement agencies, raising concerns about potential misuse. Without adequate checks and balances, the risk of harassment, wrongful arrests, or selective prosecution remains a looming challenge.

- Gender Bias and Inclusivity Gaps

Despite modernization, certain provisions retain gendered language and male- centric assumptions, particularly in sexual offences and domestic violence. There is a pressing need for greater inclusivity, both in language and substance, to protect the rights of all gender identities.

- Resource-Intensive Transformation

The digital shift envisioned by the new laws necessitates robust infrastructure, including courtroom technology, secure data systems, and forensic labs resources that remain unevenly distributed across rural and urban India. Without proper investment, the vision may falter in execution.

Merits of IPC, CrPC, IEA

- Well-Established Legal Framework

The IPC, CrPC, and IEA together formed a coherent and time-tested legal structure, providing the judiciary with a stable and familiar foundation for adjudicating criminal cases over many decades.

- Legal Certainty and Precedent

These laws had been interpreted and clarified through generations of judicial precedent, offering a deep reservoir of legal certainty and jurisprudence for practitioners and judges alike.

- Clear Separation of Substantive and Procedural Law

The distinction between the IPC (substantive offences) and CrPC (procedural mechanisms) provided clarity and consistency in the application of criminal law.

Demerits of IPC, CrPC, IEA

- Colonial Origin and Outdated Language

Drafted primarily to serve the interests of the colonial state, these laws often prioritized control over citizen rights. Many of their provisions used archaic and colonial-era terminology, reflecting priorities far removed from present-day democratic ideals.

- Lack of Adaptability

These statutes were ill-equipped to deal with modern crimes, especially those involving technology, digital transactions, and organized international networks.

- Cumbersome and Time-Consuming Procedures

The CrPC in particular was known for its complexity and procedural rigidity, often resulting in unreasonable delays, adjournments, and backlogs in trial courts.

- Limited Recognition of Victim’s Role

Victims were often reduced to mere witnesses in their own cases. The framework offered minimal support, protection, or participation rights for victims, rendering the process emotionally and psychologically alienating.

Conclusion

India’s shift to the BNS, BNSS, and BSA marks more than just legal reform, it reflects a conscious effort to realign justice with the values of a modern, inclusive, and democratic society. By shedding colonial legacies and embracing clarity, efficiency, and citizen-centricity, these new codes lay the groundwork for a justice system that is not only progressive in form but purposeful in function. The journey ahead will demand thoughtful implementation, but the foundation has been firmly set for a future where justice is truly accessible, accountable, and attuned to the needs of every Indian.

About Author:

Prof. (Dr.) Devendra Singh is a distinguished academic with dual Ph.D.s in Finance & Management and Law (Banking & AI Laws), and over 25 years of experience in teaching, research, and academic leadership. Currently Professor and Domain Head at Amity University Noida, he has authored books, published widely, and received several prestigious awards including the National Education Excellence Award. His expertise spans corporate law, banking, project finance, and AI regulations.