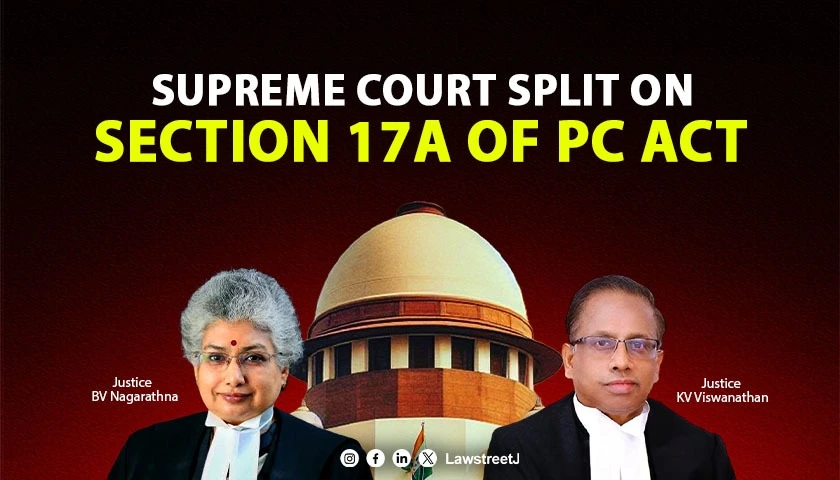

New Delhi: The Supreme Court has delivered a split verdict on the constitutional validity of Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, with Justice B.V. Nagarathna striking down the provision while Justice K.V. Viswanathan upheld it with modifications, leading to the matter being referred to a larger Bench.

The two-judge Bench delivered divergent opinions on January 13, 2026, in Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. Union of India, which challenged the provision inserted through the 2018 amendment.

Section 17A mandates that no police officer shall initiate any enquiry, inquiry, or investigation into an alleged offence by a public servant, where the offence is relatable to a recommendation or decision made in the discharge of official functions, without prior approval of the competent government authority.

The writ petition argued that the provision reintroduced protections previously invalidated by the Supreme Court in the Vineet Narain and Subramanian Swamy judgments.

Justice B.V. Nagarathna held that Section 17A is unconstitutional and must be struck down in its entirety. She characterised the provision as an attempt to “protect the corrupt” by foreclosing investigations at the threshold, thereby defeating the core objective of anti-corruption legislation.

Justice Nagarathna observed that the requirement of prior approval at the inquiry stage presumes complaints to the police to be false or frivolous, effectively preventing the truth from being uncovered.

She emphasised that while protecting honest officers is a legitimate concern, it is already addressed under Section 19 of the PC Act, which requires sanction before a court can take cognizance of an offence. She stated that Section 17A essentially resurrects executive protections previously struck down by the Supreme Court as discriminatory and arbitrary.

On the other hand, Justice K.V. Viswanathan upheld the constitutional validity of Section 17A but “read it down” to ensure independent oversight. He opined that striking down the provision would be akin to “throwing the baby out with the bath water,” as it would leave honest public servants vulnerable to “hindsight-driven criminal scrutiny” and lead to “policy paralysis.”

Justice Viswanathan further observed that the provision does not suffer from invalid classification, as it applies uniformly to all public servants based on the nature of their acts rather than their rank.

However, he found the government’s existing Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) inadequate to prevent executive bias. He directed that the power to grant approval must be shifted from the executive to the Lokpal or the State Lokayukta, whose recommendations would be binding on the competent authority.

Justice Viswanathan highlighted the gravity of the issue by referencing the Bhagavad Gita, stating that for a self-respecting person, disrepute is worse than death, and that in the age of social media, the damage caused by a public investigation is often irreversible even if the officer is ultimately found innocent.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, representing the Union Government, defended the law as a necessary statutory filter for “fearless governance” and bona fide decision-making. He argued that Section 17A was narrowly tailored and qualitatively distinct from provisions struck down in the past.

Advocate Prashant Bhushan, appearing for the petitioner, contended that allowing the executive—including ministers who may be involved in the same decision-making process—to block investigations creates an inherent conflict of interest.

In view of the divergence in judicial opinion, the matter has been referred to the Chief Justice of India for the constitution of a larger Bench to render an authoritative determination.

Case Title: Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. Union of India